Bad Ischl, a császárváros

A Zauner Cukrászdát 1832-ben alapította Johann Zauner (1803–1868), akit a neves orvos és a helyi sósvizű gyógyfürdő bécsi felvirágoztatója, Franz de Paula von Wirer, Rettenbach Lovagja hozott magával Bécsből, hogy udvari beszállítóként (K. u. K. Hoflieferant) ellássa édességekkel a nyarakat Bad Ischl-ben töltő Habsburg uralkodót és udvartartását.

A “krampusz” szó az ónémet “karom” szóból származik (Kralle=Krampen). A krampuszok a néphiedelemben félig kecske, félig démonszerű ijesztő alakok, akik a karácsonyi időszakban az Alpokban, csakúgy mint nálunk, és a környező országokban, Szlovéniában, Horvátországban, Csehországban, a bajoroknál és Dél-Tirolban, a Mikulás (Szent Miklós) kísérői.

Zsákot cipelnek, vagy kosarat, és míg a Mikulás ajándékot ad a jó gyerekeknek, a krampusz megbünteti a rosszakat, beleteszi zsákjába, vagy kosarába, és elviszi őket. Sokan azt gondolják, hogy a krampusz figura eredete a kereszténység előttre megy vissza, és az Alpokból ered. Mindenesetre Szent Miklós a 11. század körül lett népszerű Németországban, mint a gyermekek védelmezője, maszkot viselő gonosz kísérőjéről pedig a 17. századtól kezdve írnak. Az osztrákok általában azt gondolják, hogy a krampusz eredetileg egy pogány természetfeletti lény, akit a történelem során a keresztény ördöggel azonosítottak.

Dolfuss diktatúrája idején Ausztriában (1933-34) betiltották a krampusz hagyományt, és még az ötvenes években is a kormány szórólapokat osztogatott arról, hogy a krampusz egy gonosz ember. Csak a 20. század végétől lett a krampusz-kultusz ismét népszerű, és azóta egyre több helyi egyesület alakul, akik a december 5-i krampusz felvonulást (Krampuslauf) szervezik.

Hagyományosan Salzkammergutban fiatal srácok öltöznek be krampusznak. December első két hetében, és különösen december 5-én csapatosan felvonulnak, és ijesztgetik a gyerekeket (és a felnőtteket) rozsdás láncaikkal és csengőikkel, kisebb helyeken még meg is suhintják virgácsaikkal a fiatal lányokat. Ezt nevezik Krampuslauf-nak, és másnap, december 6-án érkezik a Mikulás az ajándékokkal.

Goisernt először 1560-ban említik a források, mint Geusarnburg-ot. Akkoriban ez az elnevezés a goisern-i malomra és környékére vonatkozott. A malom már több mint száz évvel ezelőtt vendéglőként működött, ahova a sószállító tutajosok éppúgy betértek, mint Rainer Maria Rilke, aki az öreg háznak még egy verset is szentelt.

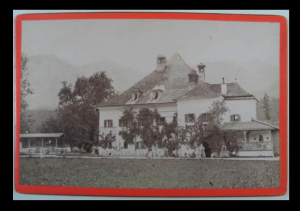

1896-ban Rilke rövid ideig Salzkammergutban nyaralt. Akkoriban az volt a szokása, hogy jegyzetfüzetébe versei mellé rajzokat is mellékelt. A fenti képen a “Goiserni malom” című verse látható a költő saját rajzával. Az épület ma wellness hotelként üzemel, ezért szinte reménytelen megtalálni a vers szövegét, mert minden keresésre a hotel reklámja jön fel. De nem adom fel, nemsokára meglesz, és idemásolom!

Ezen az 1878-ban készült képen jobban látszik az épület, de a felvétel készítőjének neve nem ismeretes.

Hallstattot hónapokig nem éri a nap, nincs elég föld a földműveléshez, és a házépítéshez, mégis egy egész történelmi kor fűződik nevéhez. Már 35oo évvel ezelőtt sóbányászatt al foglalkoztak itt, és a sókereskedelem eredményeként már az ie. 8-5. században virágzó kultúra jött létre, melyet Hallstatti kultúrának neveznek. Amikor Róma még fel sem épült, a Hallstatti kultúra már fejlett művészeti alkotásokat és használati tárgyakat termelt Európa számára.

Gosau vidékének lakói a Gosingerek többek között arról híresek, hogy lovakat tartanak. Eredetileg a só lepárlásához használt fa szállításához kellettek a lovak, de ma már ezt árammal oldják meg. Mindezek ellenére a lovak szeretete megmaradt, és tavasszal a tehenekkel együtt viszik fel őket az alm-ra, az alpesi legelőre, hogy szabadon futkározhassanak.

Gosau a geológusok között világhírű ammonit lelőhelyként ismert. Egy kis szerencsével bárki találhat megkövesedett csigát, kagylót vagy korallt, mely errefelé nagy tömegben fordul elő. Emiatt azt gondolják, hogy sokmillió évvel ezelőtt a Gosau-medence különösen gazdag élővilággal rendelkező lagúna volt. Ennek a lagúnának két maradványa van ma, a két Gosausee. Az elülső Gosausee-től (Vordere Gosausee) jó kilátás nyílik a Dachsteinre, a naplemente különösen mesés. A hátsó Gosausee (Hintere Gosausee) élettelen, és kevésbé hívogató. A nagy hegy itt már nagyon közel van, és néha egy-egy szikla legörög a mélybe. Van egy monda erről a tóról, mely valószínűleg még abból az időből származik, amikor az Ausztriában elsőként protestánssá lett Gosauiakat hitük miatt üldözni kezdték. Az ellenreformáció ellen harcoló Gosauiakat fekete lovasok kergették a hátsó Gosausee jegére, de a lovak súlya alatt megrepedt a jég, és a feketeruhás üldözők mind a tóba vesztek. A legenda szerint azóta vannak a Gosausee-ben fekete hátú kis halak, melyeket ma is “fekete lovas”-nak (Schwarzreiter) hívnak.

On the way home through the backstreets of Baluwatar I felt someone watching me. He was tall and extremely handsome. Shining blue eyes, marble white skin, rosy cheeks. A Westerner, wearing a Nepali outfit. He fixed his eyes on me, and his smile filled the grey autumn day with vibrant colours. The houses seemed to loose contours, everything turned bright yellow, orange, purple and red. I felt mesmerised, and just walked toward him as if drawn by an unknown power wondering what`s gonna happen next. When I finally reached him, he said with a radiating smile: “Jesus loves you. God bless you.”

I was staying in Kathmandu this June, trying to recover from a difficult Kailash trip. Couldn`t really do much for about three weeks, just stayed in bed, and read books to immerse in different dimensions of reality to ease the pain. One day I decided to leave my confinement, and aimlessly wandered down on Kanti Path jumping like a grasshopper in my flip-flops to avoid the bigger puddles left behind by the monsoon rain, letting the sight of the brightly sunlit brick walls and the steaming pavement fill my heart with warmth, browsing the colourful street stands offering oddities from lime juice, mobile cases, plastic knickknacks, ayurvedic herbs to piles of fruits, DVDs and knitted baby clothes. I noticed a bookshop I haven`t been to before and saw with surprise a new Samrat Upadhyay book advertised in the shop window. I got suddenly energized by recalling his wonderful collections of short stories I read the year before, ‘The Royal Ghost’ and ‘Arresting God in Kathmandu’. No doubt, I had to buy the book immediately, called ‘Buddha`s Orphans’.

Samrat Upadhyay is a Nepali writer, who is teaching creative writing at Indiana University. He is not only a master of character portrayal, but also a spiritual man, who understands even the tiniest stir of the soul (or whatever different systems of thought call the core of being). I was thinking how to describe ‘Buddha`s Orphans’, and I found that the first sentence of the book says it all: ‘Raja`s mother had abandoned him in the parade ground of Thundikel on a misty morning before the city had awakened, and drowned herself in Rani Pokhari half kilometre north. No one connected the cries of the baby to the bloated body of the woman that floated up to the surface of the pond later in the week.’ This is the axis of the novel in a way, cause and effect. The story follows Raja and people who become his family to see the effects of this tragic moment in the future, but in the same time it looks back to the past for short moments to understand the causes which led to it. We recognize ourselves in the characters replaying roles inherited from our/their parents, get to know all the joy and sorrow a man can go through, and become familiar with the turbulent events of Nepali history, which provide a fascinating historical backdrop. And when I think about it, it is more than just a backdrop, political movements and events determine and change dramatically the life of Raja. Anyway… Certain characters, feelings and thoughts burnt their mark into my mind, and after reading the book in more or less one go (only the power cut could stop me:) I felt an urge to look around in Kathmandu and take photos of places where the novel was set, secretly hoping that I will bump into the characters of the story, too. On a sunny afternoon I walked out of Thamel, down to Thundikel and Rani Pokhari lake taking photos of people and places, thinking of Raja`s immeasurable pain of missing his never-seen mother. At the lake I happened to pass by a young boy who I thought had a striking resemblance of my imagined Raja. He had so much sorrow on his face, he was so still and enveloped in his painful longing that it occured to me for a moment that I might have left my own Kathmandu reality and ‘walked into the novel’. I really wanted to take a photo, but in the same time I was so afraid to be noticed. Unnecessarily. He just stared at his own train of thoughts, never realizing my presence. It was a perfect moment when time stands still.  After another two months in Nepal I went to Beijing, and from time to time I had a look at Raja`s photo and thought of the novel when missing my friends, places, and the relaxed Nepali way of life in general. The smiles exchanged with strangers on the busy alleyways, the moments of joy when the electricity came back after a long blackout, the fresh monsoon rain cooling the heat and sweeping the streets clean. I thought I should send the photo to the author, but it felt so awkward. I`m not the kind of person to write to people I don`t know, I reasoned to myself. But one day just couldn`t reason any longer:), found the e-mail address on the internet and sent the photo to Samrat Upadhyay. His reply was so friendly and nice thanking me for this sudden surprise, that after reading his e-mail a few times I sat with the biggest shiny smile on my face for a whole day as if all the suffering and pain of the world was just fiction of ancient times. Must reeeeeeeead!

After another two months in Nepal I went to Beijing, and from time to time I had a look at Raja`s photo and thought of the novel when missing my friends, places, and the relaxed Nepali way of life in general. The smiles exchanged with strangers on the busy alleyways, the moments of joy when the electricity came back after a long blackout, the fresh monsoon rain cooling the heat and sweeping the streets clean. I thought I should send the photo to the author, but it felt so awkward. I`m not the kind of person to write to people I don`t know, I reasoned to myself. But one day just couldn`t reason any longer:), found the e-mail address on the internet and sent the photo to Samrat Upadhyay. His reply was so friendly and nice thanking me for this sudden surprise, that after reading his e-mail a few times I sat with the biggest shiny smile on my face for a whole day as if all the suffering and pain of the world was just fiction of ancient times. Must reeeeeeeead!